Creating a community in MDH developments

This sub-chapter is co-authored by Hannah Hopewell and Guy Marriage

Communities are created through positive relationships with each other across the terrain of a development. These relationships are helped or hindered by the spatial characteristics of the MDH development, its multiple interfaces with neighbours and its threshold with the public realm of the street. Positive housing communities are foundational to the social capital of urban areas and fostered though cooperation, respect, and interdependence. An MDH project can enable these qualities through considerate design of its socio-spatial realm. The housing project and the variety of relationships it gives rise to can be considered the structure around which a strong sense of belonging builds. In this way we can conceive housing provision as more than the creation of individual homes but an active agent in the advancement of civil society.

Community bonds are central to wellbeing and a thriving MDH project must prioritise social connectedness and contact with aspects of the natural environment. Simple everyday encounters with neighbours affirm mutual respect for both the similarities and differences of MDH residents and their daily rhythms. Similarly, exposure to the changing patterns of nature whether through shifting light and wind effects, the various bird life that inhabits the outdoors, or seasonal changes in vegetation cultivates comfort. Vitally, connectedness is enabled spatially and physically, and thus via thoughtful layout design and skilful detailed design. Community creation in MDH design necessitates thinking about territoriality beyond the individual dwelling and towards a spatially holistic understanding that differentiates and successfully demarcates a variety of individual and shared indoor and outdoor spatial offerings.

Commonly MDH site layout prioritises outdoor living space, or what is known as defensible space, the private territory directly associated with a particular dwelling. Councils of course regulate this form of outdoor space with minimum standards. It is critical to ensure well-defined patios, balconies and front- door spaces for positive surveillance and enjoyable outdoor experience with a degree of privacy, yet it is equally imperative to seek out opportunities within MDH design for communal space. Whilst a designer cannot prescribe the social outcomes in any particular MDH project, considerate site layout can generate a variety of shared spaces that ultimately become the decisive factor mobilising positive community experience.

So, what are the variety of communal spaces that promote community wellbeing in an MDH project? Essentially the space of community creation in the MDH project can be outlined by the following spatial types:

-

Spaces of primary circulation

The way in which residents move about the MDH development signals opportunities for social connectedness. Conceive the locations of the letter boxes, the rubbish bins, the bike and/or car parking, the lift and the variety of entrances and front doors as a social network. Design the pathway network for ease of movement with a pushchair or a bike whilst allowing the points of pause for everyday social encounters. -

Spaces of shared utility

Whether under cover or outside, an MDH project should provide space for tasks not suited for inside the house. Perhaps the development is provisioned with a shared workshop, a water storage zone, a designated space for shared vegetable gardening, a composting zone? Any or all these aspects will promote positive community building. -

Spaces of primary recreation

An MDH development should assess its location for nearby recreational opportunities. If very close to a significant park space it is likely the MDH development maximises its site coverage and height. However, if no such amenities exist nearby, the design should encompass spaces to play, kick a ball or do yoga in the sunshine either at ground level or on the rooftops. Such activities will animate life in the development promoting connections across the generations. -

Spaces of primary sociality

At the site lay out stage, and depending on the scale of the MDH development, at least one location should be designated for shared social activities. Maybe a shared kitchen, a pizza oven, a BBQ and associated spaces for groups to site will accelerate social interaction within the community. -

Spaces of primary repose

Equally the designer should provide the MDH development with a dedicated space of rest, peacefulness, or a spot to connect with nature's dynamics. It may be that the site has a tree where a bird sings every morning and a bench could be located, or a particular part of the site gets lovely light in the late afternoon or early morning. Such subtle spatial gestures within the MDH can advance the enjoyment, comfort and thus connectedness to the community.

Whilst the socio-spatial realm of the MDH development can create the conditions for positive community building and go a very long way to fostering cooperation, respect and interdependence, such spatial moves need to be coupled with community governance that supports inclusivity and collaboration.

Landscapes

‘Landscape’ is a slippery word with multiple interpretations. In housing projects landscape commonly refers to the aesthetic and material qualities of outdoor spaces across ‘hard’ landscape for built elements such as decking, paving, retaining, and ‘soft’ landscape for the vegetated areas. Landscape in this context is known as ‘landscaping’ – specific areas of land modified for human amenity purposes.

Such usage however relies on a narrow and reductive interpretation of landscape. It inadvertently treats outdoor spaces as inert and separate from surrounding environments. Landscapes here are passive and juxtaposed – an object viewed for pleasure but simultaneously revered for 'naturalness'. Yet landscapes, whilst constituted of living material and ecological systems are not natural or nature. What might be gained by thinking more broadly about the agency of landscape in the development of an MDH project?

Closer consideration of ‘landscape’ reveals its interpretation as a verb rather than a noun. Thus, not as a thing or object to be seen, but as a set of multi-scaled processes by which social and ecological relationships are formed (Mitchell, 1994, p1). Such a definition allows us to see landscape as agent with capacity to influence cultural perceptions of space, as well as transform it materially. In this way landscapes are experienced as active, connective, system orientated across their material, ecological and social dimensions.

Landscape is also that which names the complexities that exist before, with, and despite a proposed MDH site. An MDH project necessitates financialisaton of land, yet with a landscape focus the inherent ecological and cultural values that land holds are foregrounded. Such attentiveness reminds us there is no place for an attitude of terra nullius in 21st century city-making. We must acknowledge that landscape does not lie silent, awaiting the architectural subject, but in fact speaks prior to any act of design (Meyer, 1994). Such recognition forces us think analytically about the site and the interconnectedness of past and present social, cultural, and physical elements and anticipate not just what landscape looks like but what it does.

Landscape processes can and must be employed to do more than afford amenity in an MDH project. Included here are key points to consider at the start of an MDH project in order to create sustainable, just and meaningful places for living.

- Topography

Studying the surrounding landform of the MDH site will offer many clues to how the site will perform. Is it in a valley, a plain, or part of a series of hills? Topography is a key determinant of enduring urban character. Think about the world’s memorable cities such as Rio de Janeiro, San Francisco, Cape Town and how development works with and to enhance landform rather than against it. Depending upon how the site is already modified, minimising soil disturbance and adapting built form to the contour of the site will produce enduring results. Topography and orientation will also aid in determining the bulk and height of a project with the goal being to augment the coherence of landform. - Hydrology

Closely related to topography is how water moves in and through urban areas. Compose the MDH site within a hydrological catchment to learn about flows. Are there any overland flow paths, what direction to flows take, how to avoid pooling, what is the soil type and its soakage capacity? Emphasising the movement of water through the proposed development offers clues to site layout and how landscape can support water movement and filtration. (Refer to wellington.govt.nz's Water Sensitive Urban Design guide). - Vegetation

Trees are often the oldest elements in urban areas and contribute not only habitat and biodiversity by animating areas with non-human life but carry cultural narrative to enrich place experience. Trees help us orientate, they can serve as way-markers in circulation patterns within a development and its interfaces with surrounding urban fabric. Learn about the original landcover of the proposed site as this will indicate what type of trees and plants like to grow in the particular soil type, aspect and climate. Take a walk and study local street trees and nearby park plantings and gardens. Recall that trees and plants within a general area are connected by birds and bees and this unseen network is deeply significant for a sustainable urban future. Vegetation is thus critical for the resilience of 21st century cities supporting the mitigation of increasing temperatures, keeping the soil alive, and distributing water. Vegetation must be integral to MDH site layout and design strategy rather than added in the left-over spaces or to screen the unsightly. If the proposed MDH site has trees of significance can the design accommodate them, or can they be moved?

Greening

Part of the problem lies in our attitude to land development, where we separate private land development from public amenities. In reality, these two need to be worked on hand-in-hand. We need to consider the street, the footpath and the local park at the same time as the housing on the sections either side of the street. No longer can we assume that stormwater runoff can be put into a public system and sluiced out to sea, or that increasing housing density can be made without considering the ongoing effects on parking, public transport, cycle lanes and pedestrian paths. We are all in this together – we cannot consider things alone.

Greening practices are increasingly prevalent in our cities with numerous housing proposals including green walls and living roofs for both environmental and aesthetic effect. Reducing impervious surfaces and affording more opportunity for transpiration in urban areas is always positive, however such initiatives frequently fail not long after installation as they have not been designed appropriately.

(Refer to the Whangarei Living Roof Guide at wdc.govt.nz).

Outdoor common spaces

The clear trade-off is between low-density housing with extensive, unused front, side and rear yards; versus medium-density with communal outdoor space. New Zealand is not at the stage of Hong Kong, with intensely high use of space and so we can afford to – and we need to – design housing around generous, comfortable outdoor spaces for everyone. This is not just a nice to have – this is a must have.

Medium density requires a different way of approaching public space than for single family suburban housing. The age of side yards and back yards and front yards needs to be completely reconsidered under MDH. The need, or want, of people to have a large lawn for children to play on is a very outdated concept, as is the inclination for this lawn to be mown every weekend. Instead, outdoor spaces are more like to be individual, like balconies, decks, roof decks etc., as well as more communal, such as gardens or communal lawn for all to share.

Designing good outdoor space is therefore one of the key aspects to creating a successful MDH project and needs to be considered first. The Auckland Design Manual is an excellent source for MDH ideas on successful community garden design, as is that from Victoria (Australia).

Auckland H6.6.15 dictates a minimum of 20m² outdoor space for ground floor and 5m² for upper floor apartments within the THAB zone. Sadly, Wellington City Council’s draft Residential Design Guide recommends but does not require any space at all. The new Government MDRS guidelines will supercede both of those by requiring a minimum outdoor space for ground floor units of 20m² at ground level or 8m² for their upper floor deck space – but this balcony/deck requirement will not apply to apartment buildings in the six to ten-storey range near RT stops. That seems unfair, arbitrary and wrong. People living on upper floors in buildings, such as apartment dwellers, need outdoor space most of all (refer to the Standards Model Factsheet at environment.govt.nz).

Back-to-back terraced housing is now an issue in New Zealand, a hundred or more years after people emigrated away from all that – only this time it is worse. Distances between houses are reduced, affecting standards of privacy and increasing perceptions of crowding. Impacts affecting the whole environment are the result of a collective decision to maintain the suburban arrangement of detached housing with direct vehicular access to each unit, rather than reconsideration of the choice of house type to suit higher levels of density (Turner, 2010).

In these studies privacy is seen to be associated with rights of territorial control and ownership; the defence of privacy becomes a matter of protecting personal rights through which individual achievements are externally measured. Reduced private space, a quantifiable fact of higher density housing, is experienced as an “invasion of privacy”, which may be further interpreted as “theft” or “stealing” (for instance, theft of “my backyard”, or “the landscape”) to suggest an actual material loss, as in a loss of property (Vallance et al, 2005). Be very careful with your planning to avoid overlooking of the neighbour’s yard. Provide adequate space for private outdoor activities in excess of the tiny minimums shown in MDRS. Carefully planned courtyard housing can offer far better results than side yards (Marriage, 2014).

Cars and car parking

With considerable surprise to many in 2021, the Government issued NPS-UD – which proclaimed several radical changes – among them that no longer could councils require a minimum number of car parks for any housing development, country-wide. As we are a country with one of the highest rates of car ownership on the planet, that is a huge change for New Zealand. While previously housing schemes in NZ had to factor in the need for one or more off-street car parking spaces for every house or dwelling unit, this is no longer mandatory – now it is just a voluntary provision. This reflects the fact that when living in a city, having a car at hand 24 hours a day is no longer necessary. Of course, if you do want a car and don’t have an assigned car park, you’ll just have to battle it out on the streets to find a parking space.

The notion of a council paying for a public street and then letting people park on it for free is also a concept that is fast disappearing: why should the ratepayer have to pay for the cost of a public place (the roadway) and then let people park a piece of their private property (a car) there for free? Those days are numbered, and many car owners will need to reset their minds. Public ownership of land implies public space being available for all, not locked up as parking spaces for most of the day. Those that think they have a right to the use of the berm outside their suburban property are quite simply wrong.

The good thing about this as an outcome is that the developer can now spend more money on your house, or afford to provide a common space for all, or lower the cost of the development, rather than waste money on an extra room for storing a hollow steel and plastic sculpture for most of the time. Many inner-city apartment dwellers simply don’t want a car, and many don’t own one.

Car sharing is becoming more feasible as an answer to transport: self-driving cars becoming less so. Major centres in NZ now have a choice of car-share schemes like CityHop or Mevo. Car sharing may be tied into an MDH development, with some buildings allowing parking for one or two car shares only, rather than a car park space for every unit.

Urban development also requires thought and space to be given to alternative means of transport like bicycles and e-bikes, motorbikes and electric scooters, cargo-bikes and skateboards. Some of these can easily be taken inside the apartments, but many of them will need ground-floor accessible parking and charging space (e-bikes especially are too heavy to lug up stairs).

Transport oriented development

TOD is a clear driver behind the NPS-UD, with the requirement for maximum height limits to be raised within walking distance of public Rapid Transit (RT) stops. It is only recently that Auckland’s train network has become a Rapid system, and Wellington is still arguing over whether they will have an RT system extending through the city as well, while Christchurch, Tauranga and other Tier 1 NZ cities have no RT at all. Buses running with the traffic on city streets don’t count as RT. Despite that, NZ cities must start planning for RT right away, as a future is anticipated when many people will live without a car. The Government is insisting that MDH development should happen in all areas within walking distance of a RT stop, which will heavily affect the look and feel of our cities into the future.

Overseas, TOD is a common planning phenomenon. On the other side of the Pacific Vancouver has high population growth and massive uptake in TOD. Centred around the Sky Train aerial light rail routes, each station stop has a growing circle of very tall residential buildings. 10, 20, even 30 storeys high, this TOD development ensures that all the recent inhabitants can get wherever they need via the high-speed RT system. Auckland is planning for massive growth around stations created by the CRL, and for moderate growth around the existing suburban train stations. If Wellington or Christchurch ever get inner-city RT systems, similar TOD growth patterns will occur.

Figure 4.1

Transport oriented development, Vancouver, BC. New apartment buildings crowd around the stops of the SkyTrain.

Image Source: Guy Marriage

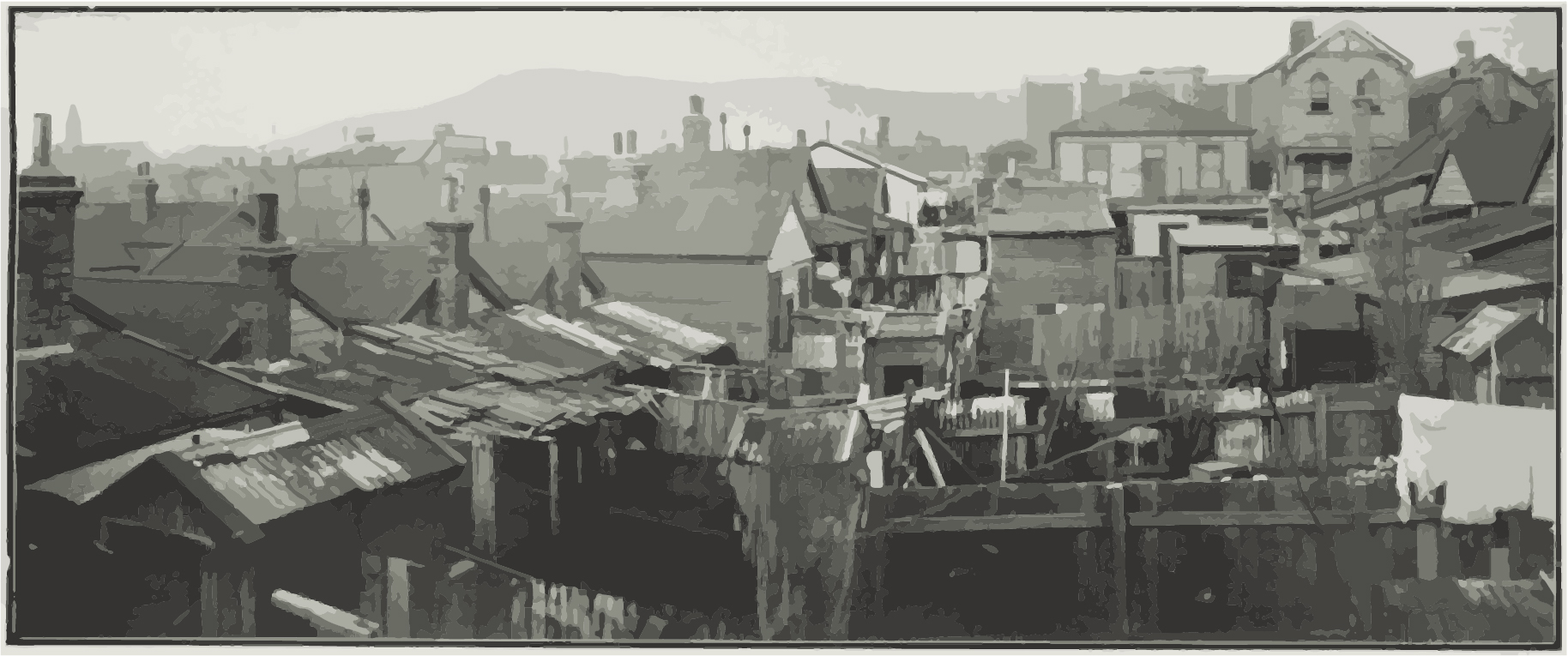

Slum no more

Slums are caused by overcrowding, poor hygiene conditions, and the construction of substandard dwellings. The UN warns that anywhere there are more than two adults sharing a bedroom indicates overcrowding and possible slum conditions. By that measure, many of our existing communities are already experiencing slum conditions. While in some countries slums may be visible by their informal dwellings (like the favellas or barrios), in NZ we are more likely to have people living in their cars, building tiny houses, or sleeping multiple people in each room, rather than constructing cardboard cities under motorway overpasses or corrugated iron shanty-towns at the city limits. But we are only one very short step from our housing crisis developing into slums.

We can expect that cities will always have a degree of what planners might call unevenness. Slums come about when cities are subject to excessive growth pressures, when sewerage and transport infrastructure cannot keep up with the growth and when there is a shortage of usable land. Does that sound familiar at all? Ben Wilson’s excellent book Metropolis permits a sobering comparison with Auckland’s housing issues when it notes that:

“Cities like Manchester and Chicago grew so quickly, and were so obsessed with profit, that they lacked the civic amenities, sanitation, public spaces and communal associations that had defined cities since they first emerged in Mesopotamia 6,000 years before. In slums such as Angel Meadows [Manchester’s most notorious slum], houses were built by ‘the horrible system of huddling cottages together, back to back, in streets without drains, or any means of carrying away the refuse from the doors of their homes’. Multiple- occupancy was common (the average Irish slum house had 8.7 people); overcrowding forced many casual workers into damp shared cellars in lodging houses where they often slept three to a bed. There were two outdoor toilets for every 250 residents of Angel Meadow.” (Wilson, Metropolis, P214).

We have actually had slums constructed in New Zealand before, around a hundred years ago, despite people migrating to NZ to get away from overcrowding. Substandard housing sprang up quickly surrounding the inner-city suburbs of both Auckland and Wellington and existed for many years. How do we stop this happening again? The simple answer is to not construct substandard buildings today and to not provide inadequate amenities and infrastructure.

Sadly, inadequate housing is already in our society. Some of these substandard houses are the ‘leaky buildings’ that have been built in NZ for the last 40 years. Amazingly and sadly, despite being a problem issue identified in the late 1990s, poor design and shoddy construction mean that leaky buildings are still being constructed all over NZ, especially in the Auckland/Tauranga region. Building quickly and badly to solve an immediate problem is a waste of money in the long run. It is very hard to improve a building from a slum dwelling of last resort into a desirable residence – it is far better to build better in the first place.

Another problem is buildings of substandard size. While most developed nations around the world have legally mandated national minimum housing sizes, NZ has none. Auckland has some space minimums, introduced a decade ago, but nationally we have none. Perversely, even the brand new MDRS have no standards for size. Slowly, some individual councils are putting in place some minimum overall standards (see Table 3.3). Without any national legal minimum housing sizes some unscrupulous developers are constructing low-ceilinged, tiny-roomed dwellings and selling them to a desperate public as long-term housing solutions. Small can be good, but to be small it needs to be very clever in its design and well-built in its execution. If housing is small in size, poorly designed and badly constructed, it’s only real future is as a slum. Why allow the construction of housing we know is destined to become a slum?

Figure 4.2

"Back of houses in Haining Street". Slum in Te Aro, Wellington, 1911.

Image source: Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, NZG-19110719-21-3